The Flow of the Water

A History of Warner Park

By Trish O’Kane

March 2007

With two feet of snow still on the ground in Madison, the air was biting hard on the weekend we came to buy a house. We flew in straight from Alabama, where a tornado the night before pummeled the town of Enterprise, crushing and killing eight high school students huddled in a hallway. Alabama had become our refuge after we lost a home to Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans, but now Alabama too seemed possessed by some vengeful weather demon, with ear-splitting thunderstorms, frequent tornado warnings and disappearing winters.

Our local real estate agent was showing us 12 houses that Saturday. With motherly Norwegian efficiency, she shuttled us around the west side in her warm SUV. She’d worked hard but this neighborhood was out of our price range.

The sun was going down. We were weary and desperate. There was one house left. It was near the airport in an area we knew nothing about.

It was a simple low-lying white ranch with an open floor plan and natural light. I stood in the middle of the living room and gazed out the huge front picture window.

A scattering of red pine, red oak and black walnut trees stood across the street. In the middle of a small clearing there was a lone white spruce, it’s Christmas tree branches laden with snow. It was a stoic tree, with neat clear lines, not the gnarled southern live oaks dripping with Spanish moss that I loved. The snow made everything look so peaceful and still.

In my tropical eyes, it was a Christmas card–a snowy sanctuary, a tastefully preserved slice of wilderness next to a cozy home. I half expected a bear to walk through the clearing with a “Welcome” sign.

We returned the next morning to check out the dog park nearby. From the house we tromped along Warner bike path as it wound through two groves of ash, hackberry, pine and oak, rimmed by thickets of staghorn sumac.

In the dog park a sign laid out the rules. The park was well-fenced and a circular trail ran along its perimeter. It was on the edge of the lagoon and the water was frozen, quiet, no dog-eating alligators lurking under there. A marshy island in the middle of the lagoon seemed to signal that Wisconsinites respected wetlands.

People came in and out, carefully closing gates behind them, leashing and unleashing their furry wards, even picking up their poop in biodegradable baggies.

If people obeyed rules in dog parks, it meant they obeyed building codes too and environmental zoning laws. It meant rationality and planning and order instead of a chaotic landscape of swampy horror where 11.5 feet of chemical soup filled your house and dead neighbors floated around in life preservers and the National Guard had to kick down your swollen front door to search for bodies.

That day in Warner Park I perceived a truce between man and nature. This was a sensible landscape, where people, dogs, even the water, seemed to know its place. We made an offer on the house that very day.

We moved to Madison in late April. The ice was gone and a fresh crop of fuzzy goslings nibbled at the lagoon’s edge. The Christmas postcard world was fast turning green. The first night at dusk we sat on the couch and stared out the window, agog, toasting our turn of luck with champagne.

“Look!” I shouted and pointed across the street.

Three large four-legged shadows slowly wove in between the pine and oak, white tails flashing.

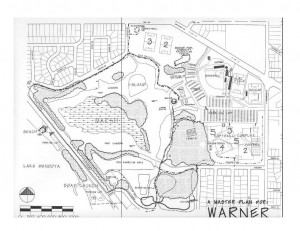

For this paper I decided to follow my gaze out our living room window, across the street, through the meadow that was once high prairie, past the forested areas where the deer browse and down through the gently curving Olmstedian landscape of Warner Park. I started my research by looking at the land and the farms that once occupied it. The land led me down the same path I take every morning with my dogs, from the high ground to the low ground, and to the waters of Warner Park Lagoon. I learned that I live in a watershed where all the runoff from seven storm sewers in my neighborhood runs down into the lagoon. So this paper is really about the water, how it has flowed and how people have tried to control it, for better or worse–and in the case of Warner Lagoon, for worse.

The Land and “the Park Men” Who Shaped It

Warner Lagoon is in the township of Westport, now part of the city of Madison in the area known as the Northside. Westport was organized in 1849 and named by Irish emigrants who came from Westport, County Mayo, fleeing the potato famine.1 At the height of the famine, when over a million were dying, Irish people walked across the island to board a ship in Westport, the country’s coastal escape valve to the New World.

In 1874, Daniel S. Durrie, the Wisconsin Historical Society’s first librarian wrote that the northern and western portions of Westport township were “principally prairie–the rest marsh and timber.”2

The 1899 Plat map shows the railroad tracks built by Chicago and New Western Railroad in 1864 that now border the dog park at the west end of the park, and the “State Hospital for the Insane,” now the Mendota Mental Health Institute to the north west.3 The same map shows that most of Warner Park’s land was owned by three different farmers: J.P. Woodward, the Sachtjen family and J. Castle. According to the Dane County 1976 Atlas, our house is located on lot number 25 of Westport, T 8North – R 9East, section 36, in the furthermost southeast corner.

Warner was one of the last parks sponsored by the Madison Park and Pleasure Drive Association (MPPDA)–a private organization that preceded the city’s Park Division. On January 12, 1893, the Wisconsin State Journal published a letter to the editor by “one of Madison’s original park men,” W.R. Bagley, an MPPDA founder. In the can-do language of the Teddy Roosevelt progressive era, Bagley laid out MPPDA’s vision:

Warner was one of the last parks sponsored by the Madison Park and Pleasure Drive Association (MPPDA)–a private organization that preceded the city’s Park Division. On January 12, 1893, the Wisconsin State Journal published a letter to the editor by “one of Madison’s original park men,” W.R. Bagley, an MPPDA founder. In the can-do language of the Teddy Roosevelt progressive era, Bagley laid out MPPDA’s vision:

“The proposition on the part of our public spirited citizens, to organize an association for the purpose of improving and beautifying our city, is a grand move in the right direction…Every space of ground within our limits, and especially upon the shores of our lakes, not immediately connected with residence, or needed for building or business purposes be improved, beautified and made attractive for the enjoyment of the public…We are tired of the old song ‘Nature has done much for Madison.’ It is a reflection on our enterprise and public spirit; let it rather be said, ‘Nature has done much, but man more.’ Let us then cease our inactivity, and join forces with Nature, a co-partnership arrangement…Because we have beautiful lakes, with magnificent scenery around them, is just the reason why we should provide suitable, comfortable and cleanly places…These ends of streets, today the home of the oyster can and the ash heap, now useless and unsightly, with proper repair and care would be genuine pleasure resorts, attractive and enjoyable to everybody, enhancing the value of property, and beneficial to the public health…”

Bagley’s “unsightly street ends” were, in fact, the edges of marshes that stretched out into the lakes. These marshes were dumping grounds for trash and breeding grounds for mosquitoes. Other prominent citizens and visitors at the turn of the century expressed similar opinions regarding the lake shore. In 1902, one visitor described B.B. Clarke Beach as “…made up of a steep bank, ashes, tin cans, stagnant water and irregular filling. It is a rallying point for all the old footwear and other refuse of that part of town. It is a breeding place for bullfrogs and disease.”4

With epidemics killing thousands in New York and New Orleans, dirty water meant disease and death, and this vision of wetlands as a public health menace persisted until the 1950s. In May 1951, the Madison and Wisconsin Foundation (affiliated with the Wisconsin Chamber of Commerce), described the evolution of Madison’s parks: “Beautiful Tenney Park…was an unsightly, odorous cattail marsh until good citizen Daniel K. Tenney transformed its 44 acres…Vilas Park…was largely a low-lying swamp…Brittingham Park…was a green scummed, malodorous, cattail marsh…Olbrich Park…was mostly a low-lying, unattractive bog…”5

In the early 1900s, the seeds of Warner Park were sown when the MPPDA decided to try and buy a popular white sand beach on the shoreline. Ernest Noble Warner, a progressive Republican who was MPPDA president from 1912 to 1930, appointed a special committee to acquire the beach for the public from the Woodward farm.6 Shortly after these efforts, Warner died suddenly in a car accident.7 Because of his public service to Wisconsin and his interest in this particular park, the MPPDA named it after him.

The Depression slowed down the MPPDA’s fund-raising to buy this land.. The MPPDA kept making payments to the Woodwards for the farmland but in 1937 it still owed them $10,700.8 By 1939, the MPPDA was able to turn over the first seven acres of Warner Beach to the city of Madison, after the creation of the city parks division.

Just east of Warner Beach, the area was a marshy lowland called Castle Marsh. According to Jack Bell, Dane County Conservation League (DCCL) historian, the installing of the Tenney Park locks in 1912 created Castle Marsh when lake levels rose by approximately five feet.9 The high water flooded J. Castle’s fertile farmland (Castle is one of the original farmers in the 1899 survey) and also acreage belonging to Herman Weddig, just east of the railroad tracks. Before 1912, this low area served as a catch basin for over 400 acres of farm land in Westport.

The Tenney Park locks turned it into a much larger marsh that extended over 13 acres. According to Bell’s unpublished written account, “The Castle Marsh Story,” northern pike, large mouth bass, carp and bullheads soon discovered the marsh and it became a popular spawning ground and nursery. High water levels in the spring allowed the pike to swim in to spawn. Before the water level lowered in the fall, the adult fish and their fry had time to return to Lake Mendota. When they finally entered the lake, large mouth and yellow bass were waiting for them, Bell wrote, and their stomachs became so stuffed with little pike that they could no longer swallow.

In 1953 the Dane County Conservation League found that Castle Marsh was “the last good spawning ground on Lake Mendota and the only natural rearing pond in the area.”

Local fisherman Jack Hurst agreed and told me that in the 1950s “you used to be able to walk on the fish. It was one of the best areas for the fish. I live a couple of blocks from there. There were no houses. I could see 75 pheasants at a time running around.”10

Of Pike and Men

Of Pike and Men

With the post WWII building boom, housing developments began replacing farm land on Madison’s north side, as the township morphed from rural to urban. By the 1950s, the city wanted to ramp up park development to serve this expanding population; it purchased the Moore farm in 1953 and the Mary T. Rieder farm in 1955 (the Rieder farm sat right across the street from my house, where the trees are today). A 1950s article in the Wisconsin State Journal described the future park site as “a swamp area in the section recently annexed to the city from the town of Westport.” Park Superintendent James Marshall mentioned “the low characteristics of the land” and said the city would dredge a lagoon there within five to ten years.11

In 1955, the Wisconsin Conservation Department (now the Department of Natural Resources-DNR) bought 13 acres of Castle Marsh to protect the pike while the city developed the park. Documents in the DNR’s “Castle Marsh” file show that the city and DNR agreed that a lagoon could be created for recreational purposes while preserving enough wetlands to support the pike. This agreement is why part of Warner Park (the Castle Marsh area) is still owned by the DNR today although the Madison City Parks Division administers it.

In 1958, the city dug the first drainage ditch. “One of Madison’s finest parks is planned for the raw land enclosed within the dotted lines in the photo above…” reported The Wisconsin State Journal. The article ran with a photo of the “raw land” with the dotted line representing the new drainage ditch. A baseball diamond was installed and the city was preparing to seed the area with grass.12

By 1959 there was already evidence in the DNR file that the pike were in trouble. Just one year after the baseball diamond was installed and the city started seeding the turf, Wisconsin Conservation Department official Ed Owen filed this report:

“On the afternoon of Thursday, April 16, 1959, I personally observed the existing conditions at Castle Marsh in general and for the presence of northern pike specifically….The water level in Lake Mendota appears comparatively high and ice slivers are packed upon the surface waters of the Lake for a distance of one-fourth mile from shore across the entire bay containing the outlet of Castle Marsh. The water in the ditched outlet of Castle Marsh as it passes through the beach area from the lake edge to the railroad tracks underpass fills the 36″ diameter culvert with 30” of water. There is a very slight flow of water from the Marsh out to the lake in this outlet channel…There was no evidence of northern pike spawning. About 5 acres of the marsh area proper as well as the new ditch through the marsh area was open water…No fish or fish activity was observed in the marsh waters outside of the channel area. Mr. Al Koppenhaver advises that on a recent visit by himself to the Castle Marsh area he found the water extremely high on the lake side and water flowing from the lake into the marsh area. This undoubtedly adversely affected any northern pike spawning run which might have taken place by preventing the current from reaching the lake from the marsh. Mr Koppenhaver did not observe any northern pike during his recent visit to the marsh area.”13

There was another water source that officials in both agencies could not contain and that was increasing in volume faster than they planned for–storm runoff from all the new housing developments.14 They decided to protect the lake and reroute the runoff into Castle Marsh, lengthening the flow distance to the lake by 1,100 feet. On April 11, 1961, Conservation Department official Elmer F. Herman reported:

“…the storm sewer drainage of the uplands to the north and west of the WCD marsh ownership must have a natural outlet to Lake Mendota. It is felt that the routing of this run-off drainage per the easement provisions rather than a more direct route will greatly reduce any future sediment damage to Lake Mendota proper. The City of Madison Parks Commission has fully cooperated with us to date on our tentative future plans for the retention and development of northern pike habitat in this entire marsh area and at this time there is mutual agreement as to future coordinated City-Department development of this marsh…the coordinated procedure…consists of the following:

1) City to eventually lagoon the entire marsh for public recreation with proper slope on lagoon edges to promote the spawning of northerns, establish the proper channel depth of the lagoons for northern pike fry and fingerlings and natural channel bottom drainage gradient to marsh outlet.

2) City to provide for upland subdivision area drainage to protect Lake Mendota…

3) City to install a settling basin where storm sewer water enters marsh. This the city will dredge out periodically to keep it functional. The city will also maintain marsh outlet channel into Lake Mendota and provide a lake breakwater at its mouth to keep it from silting shut…”

Within nine years, the DNR recognized that the above plan was unworkable but by then the city had already dredged a 27 acre lagoon. In a DNR memo dated September 23, 1970, John G. Brasch wrote: “Due to residential developments around the perimeter of the entire marsh area…it became apparent that control of water levels over the entire marshland would be impractical…”

The Parks Division and DNR

During the dry July of 2007, Madison Parks Conservation Resource Supervisor Russ Hefty had the same concerns about the pike as Ed Owens had had 47 years earlier. Hefty thought lake water levels were too high to allow the pike to get in to spawn, even under drought conditions. He lowered his kayak into Warner Lagoon “just for my own curiosity.”

“The pike need sedge meadows to spawn, fine grasses they can easily get into. I found reed canary grass in Warner Park. Pike eggs suffocate in the soft sediments around reed canary grass. In the reed canary grass, the water was still six inches higher in elevation, even in drought time. There were hybrid cattails at the right elevation, but cattails are not good for pike. I don’t know where they are spawning.”

Hefty said that pike historically go to very shallow areas, 10 inches to one foot, and the backs of the fish will stick out of the water. The eggs need spring flow to provide oxygen which comes from little rivulets that flow into lakes and marshes.15

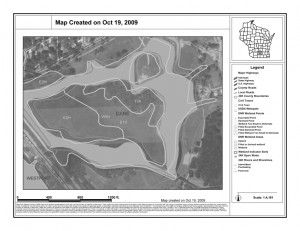

Hefty suspected that the reed canary grass growth started during the housing development boom in the 1950s, with an increase in nutrients carried by storm water. Reed canary grasses are flood-tolerant and love high nutrient storm water while sedge thrives in low nutrient water. Hefty has been tracking the degradation of Cherokee Marsh for years by analyzing aerial photographs and he has documented a detrimental sedge to reed canary transition. He told me to search aerial photographs of Warner Park for dark areas that bleached white over the years. He’d found in Cherokee Marsh that dark areas often signaled sedge and that bleaching out in aerial photos was the signature of reed canary grass.

I tried to analyze aerial photographs of Warner Park from 1937 to 2000. Finally I took the photographs to Hefty to borrow his expert eyes. This is what he said:

1) 1937: looks like sedge meadow. No open water visible.16

2) 1949: rectangles of land that Hefty thinks signal mowing for marsh hay, typical of what farmers used to do with a low prairie.

3) 1955: splotches of bright white appearing-the signature of reed canary grass. It’s not ice because the photo was taken in July.

4) 1962: the white lines are the start of the city drainage system as the city deals with increased storm runoff from new housing developments. The water is beginning to appear.

5) 1976: huge change–the lagoon is clearly visible and there are bleached out swaths on the marshy island.

6) 1980: “Now it’s reed canary city–a disaster,” Hefty said.

From analyzing these photos and from his field inspections, Hefty described Castle Marsh as “a shell of its former self. It looks like it was a wet prairie, sedge meadow and shallow emergent marsh and it’s now converted to turf or open water. There is very little left of the original habitat of the 1940s and 1950s.”

Hefty warned against harsh judgments towards park planners: “People had different ideas back then. There was no Earth Day. A wetlands was no-land–people didn’t value what they were. They viewed what they were doing as an improvement.”

Kurt Welke, the DNR’s Fisheries Biologist, would not definitively say that there are no pike spawning in Warner Lagoon, although his description of the lagoon’s problems matched Hefty’s assessment.

“Warner Lagoon is an artificial construct. The mindset back then was we have this public asset, an opportunity for angling. It has diminished in quality and so has its value.”

As regards the pike, Welke said “now their presence is largely artificial and dependent on human inputs. There’s not much spawning habitat left for the pike in the Yahara Chain.”

Welke said the pike might still be going to Warner Lagoon to spawn but doubts all the pieces are in place in order for the pike to reproduce. Even if the females have the habitat to lay the eggs, do the males fertilize them? Can they mature successfully? Can they hatch and can the fry mature and survive predation? The habitat has been so compromised by sediment that Welke thinks the answer to these questions is negative, since the pike is a habitat specifist, not a generalist like carp or bluegill.

“Look at how the pike swim and what they need. We’ve altered things too much for them.”

Fixing it: The Physics and Politics of Fluid

Like Hefty, Welke believes the main contributor to degradation is increased storm run-off due to construction in the 1950s. The Yahara Fishing Club (mainly Jack Hurst) has been pressuring DNR and city engineers to try and improve the health of the lagoon and mitigate this run-off. In 2006, the city and DNR met to discuss possible fixes and they agreed to build limestone settling basins. The first basin was put in last year; when the city cleaned it out there was 66,000 pounds of sand in it. Welke said this is because most of the pollutant load is sand from winter roads, mixed with phosphorus from lawns, chloride, and automobile grease.

“Storm water in Madison is a pretty nasty soup.”17

Welke explained that storm outflows are a common problem in many municipal watersheds. Typical storm sewers handle a huge volume of water and they do not have the capacity to remove suspended components. When they do have traps or sumps, the heaviest components are trapped and the city can put separators in the pipes to slow the water down. Welke emphasized that even then it is still very hard to get the suspended particles out. Time and space is needed to slow water flow down and water must be quiet in order for the lightweight components to settle.

“The city can only do so much. Everyone has a role. The physics of fluid are a real problem in Madison. We don’t have the physical area big enough to treat the water like the retention ponds on the west side. In downtown for example, where are you going to put a catch basin? There’s no real estate left.”

Welke said we need to prevent pollutants and sand from getting into the storm water to begin with and implement more green strategies like green roofs and rain gardens.

“When the city was plumbed 100 years ago, the mindset was that water is bad because of water-borne disease, so let’s get rid of it. Make it dry, make it high. Now it isn’t just the water that’s problematic, it’s what’s in it. The fixes today are only as good as technology allows. You can only treat so much water coming through at a high rate of speed. And if you slow the water down, then people’s basements will flood.”

Better erosion control and more regulation is needed as well, according to Welke. Commercial developers in Madison are subject to strict guidelines every time they move any soil. But there is no legal jurisdiction over single family dwelling construction and no erosion control, so the city is losing too much soil.

“This is a multi-faceted, very complex problem that is due to urban runoff, agriculture, suspended contaminants and the disconnect between single family dwelling versus commercial construction.”

Conclusions: Lessons from the Land and the Water

1. Nothing is as it appears–we live in a layer cake of ghost landscapes: What looked to me on that first March day as a slice of tasteful wilderness is a manmade construct, totally manipulated and dependent on man and his machines for its survival (dredging and harvesting of invasives like Eurasian watermilfoil). That day, with no prior knowledge of the place or its history, I projected my needs onto this new landscape, based on my experiences and selective memory. As I stood at the water’s edge, seeing calm and beauty in its frozen surface, I did not know that just underneath lay thousands of dead fish that had suffocated because of a lack of oxygen in the shallow water. By the time we moved in a month later, the ice had melted, the fish kill had been discovered and the dead fish had already been removed (it took park staff a few weeks according to press reports).18 I would never have known about this large fish kill, a three minute walk from my home, if not for this research paper.

2. Every marsh, wetland and lake needs a fairy godmother: Our planet needs more people like Jack Hurst who is pushing the city and the DNR to improve Warner Lagoon, stewards who track the changes that happen to a piece of land or a body of water over a lifetime. Without these earth historians, the name-keepers and game-keepers, we all suffer from what ecologists call “baseline syndrome”: we do not even know what we are losing because we do not know what was there before.

3. Too many cooks spoil the lagoon: After studying the DNR file and after lengthy interviews with Welke and Hefty, I believe that everyone was responsible and no one was responsible in the DNR-City historical partnership to manage the marsh. I asked them about this partnership and how it worked or didn’t work. Welke said: “The problem is that things slowly happen. The city had to get rid of water and we let them.” Hefty said: “No controversy there. They’ve done nothing and we’ve done nothing. Now the fishermen are bugging them and our engineers.” Both of these men obviously care about the environment and both seemed frustrated. Welke’s final comment: “Societally we choose an economic endpoint before we understand the inherent value in a slough full of ducks. These things don’t pay the bills, eventually it comes down to money. Think about our consumptive culture. What we value is pushing money back and forth across the table.”

4. We need to radically change the way we view property, the nature of water and of flow: Water is about impermanence and constant change, yet we build railroad lines and utilities and permanent houses on shorelines that should ebb and flow, even disappear. We need to look at what flows through land and take responsibility for the health of the water.

5. Man has imposed a hierarchy on nature and in that hierarchy lakes rate higher than wetlands: The DNR’s documents from the 1950s through the 1970s show that Castle Marsh had no value on its own–it was valued simply because of the pike. A wetland or marsh is an ambiguous netherworld for fish and birds. It does not fit into what Hefty called our “golf course pond mentality.” You can’t race a speedboat through it. These are shadowy, quiet, shapeshifting places that are neither land nor water. In parks management lingo they are places of “passive recreation” such as birdwatching, kayaking and hiking. When I stood in line at the DNR to pick up the Castle Marsh file, examining the walls covered with mounted deer and the only woman surrounded by men applying for hunting licenses (one clutching a dead turkey in a plastic bag), it struck me just how gendered this hierarchy still is.

I follow the old railroad tracks down to the hidden part of Warner Lagoon, the part you don’t see when you go to the dog park or to Warner Beach although it is the Lagoon’s most vital artery, the outlet and storm pipe that Ed Owen described in 1959.

There is a pool of water about 25 feet wide between the CCC-era keystone railroad arch and the storm drain emptying into the lake. The three foot wide storm pipe that Owen described is under Woodward Drive (Hefty said the pipe is crumbling underneath the road and he’s warned the city engineers about it). The water in the pool between the railroad and Woodward Drive is a sickly brown-grey and looks stagnant; nothing is flowing today. A line of bright blue stains the stones and earth around the circumference of the pool, as if someone has dumped paint into it. A red cotton shirt hangs on the dried brush around the pool and a pair of aluminum cans lie scattered on the slopes along with a Culver’s frozen custard shake cup.

I am trying to finish my paper, but I have more questions now than when I started:

-What was the role of these railroad tracks in changing this watershed?

-Castle Marsh was created when lake levels were raised so its creation destroyed other wetlands. Is there some kind of balance? What is a real wetland?

-It looks like the pike are gone, but we have a pair of sandhill cranes visiting and a lot of geese. What is the balance? Are the animals winning or losing? Which animals are better and for whom?

-Did the city comply with all that it promised in the 1950s and 60s as regards protecting the marsh? Are the catch basins being built today the basins they promised to build back then? Did somebody drop the ball? If so, who, when and why?

-What are the problems that arise when two agencies are responsible for one small piece of land and its complex resources?

-What is the soil history of Warner Park?

I close my notebook, scramble down the bank and cross Woodward to examine the outlet into Lake Mendota. There are often Hmong fishermen there because of all the nutrients in the water. But there are no fishermen today, just me and a small black-headed bird in hot pursuit of a white-winged moth. On the second dive bomb over the outlet, the bird catches the moth in its beak. It flits to the nearest naked tree branch and gobbles it down.

This paper was written by Trish O’Kane, PhD student in environmental studies at UW-Madison, for Professor Bill Cronon’s class, American Environmental History 460. 11/26/2007.

Footnotes

i Today Westport is the site of the National Famine Memorial. Some of the last names from Westport, Ireland that are prominent still today in Westport, Wisconsin are O’Malley, MacBride. From “County Mayo: An Online History,” http://www.mayo-ireland.ie/Mayo/History/H18to19.htm.

ii “A History of Madison, the capital of Wisconsin; including the Four lake country,” by Daniel S. Durrie, 1874, pg. 412.

iii From “The Railroads of Wisconsin 1827-1937,” The Railway & Locomotive Historical Society, Inc. Boston Massachusetts, August 1937, p. 8.

iv “Parks & Open Space Plan,” Madison, Wisconsin, page 2, 1984.

v “Madison’s Parks,” Madison and Wisconsin Foundation, May 4, 1951. The press release also lists Warner Park but only describes “2,200 feet of sandy beach that is unexcelled.” It does not mention any malodorous marshes.

vi I went through the Frederic Risser Papers in the Historical Society Archives (Risser was Warner’s son-in-law), where there are a few thin files containing some of Warner’s personal correspondence and a few news clippings about him. There was nothing on Warner Park but Warner’s papers show what an engaged citizen he was. There was a large black and white photo of a dairy farm being dismantled in the file. It had no identifying information on it and the archivists had no clue as to whose farm it could be. Since Warner donated much of his own dairy farm on Madison’s west side to the city for park land (“The History of Warner Park,” Northside News, October/November 1999), I believe that the photograph may have been of his own farm but I am not sure. I was hoping that it was a photo of one of the farms sold to create Warner Park but I could not find that out.

vii “Warner Park History,” Madison Parks Division website: http://cityofmadison.com/parks/major/warnerhistory.html.

viii Ibid.

ix Bell has been a member of the Dane County Conservation League for 50 years. He generously gave me “The Castle Marsh Story,” his unpublished history based on interviews and DCCL’s files.

x Interview on November 19, 2007.

xi “Sought For Park: Warner Beach Area Negotiations Open,” Wisconsin State Journal, 1953? I do not have an exact date or year for this article because it was given to me by Ann Waidelich, a local historian. Ann generously shared her Warner Park file with me and it contained many old clippings such as this one but the photocopy simply said “1953?”

xii City Takes First Step to Create Warner Park,” Wisconsin State Journal, August 10, 1958, pg.16.

xiii From DNR’s “Castle Marsh” file.

xiv I am speculating that they did not anticipate it based on my readings of the memos and also based on an interview with Kurt Welke. Ed Owen is dead.

xv Hefty believes the deep water is a problem for the pike all over the Yahara River Basin. He’s been looking for the pike for five years to see if DNR’s efforts to protect them are working and he cannot find pike fry in wetland areas with the exception of Pheasant Branch Creek. Hefty says that any pike left in Madison are only because of the massive amounts of fry that the DNR is releasing from hatcheries. Scientific data is needed to find out if and where the pike are still spawning. Hefty recommends a pike program modeled on a successful experiment in Minnesota where tiny radio transmitters were attached to female pikes to track where they were spawning.

xvi When contrasting the 1937 photo with the 1990 photo, the explosion of housing and commercial development along Sherman Avenue is greatly apparent. In 1937 there is a patchwork quilt of different-sized rectangles of cultivated farmland. In 1990, these large rectangles have been carved into thousands of tiny rectangles for individual homes.

xvii Welke is using funds from an Environmental Damage Compensation Grant to pay for the Warner catch basins. Welke described it as “mitigation” funds. The money came from a $36,000 fine that the developer/owner of the upscale Bishop Bay housing development had to pay for putting a huge amount of sediment into the lake. Welke is using approximately $10,000 for Warner Lagoon.

xviii “Fisherman takes a stake in the lake,” by Dorothy Wheeler, April/May 2007, Northside News. A September 2007 report by Dane County’s Land and Water Resources Department on the health of four ponds found that Warner Park “was the only pond that lacked clear water and had phytoplankton blooms.” The report also found low dissolved oxygen levels. I hope this doesn’t mean a repeat fish kill in 2008.

You must be logged in to post a comment.